The problematic politics of LGBT+ suicide prevention in the UK

Note on terminology: In this blog, I am the term using ‘LGBT+’ as it is the term used in the paper.

To understand how health and social policy affects citizens, perhaps we first need to understand how the ‘problems’ that the policies aim to ‘solve’ are formulated. Such policy problem construction happens in a broader social and political context: ‘social policy does not emerge in a vacuum…Social policy is always shaped by the concerns, interests, ideas, and material conditions amid which policy makers find themselves. It draws on prevailing discourses and available narratives’ (Cameron, 2018 p.51).

For example, the 1957 Wolfenden Report drew on prevailing discourses about homosexuality being a mental illness. Research at the time revealed that the Wolfenden Committee included psychiatrists who argued that medical treatment could be preferable to imprisonment for gay or bisexual men (Scott, 1958). Although the Report resulted in momentous legislative reform that decriminalised male homosexuality in England and Wales, the policy problem of homosexuality was partially grounded in a sickness discourse.

In this paper, Hazel Marzetti and colleagues (2023) are concerned with the policy construction of the LGBT+ suicide ‘problem’. Reporting on the findings of research that was conducted as part of a larger project on the politics of suicide and suicide prevention in the UK, they explore LGBT+ suicide as discussed and represented in UK suicide prevention policies and parliamentary debates.

Social policies have the power to construct and maintain dominant narratives and discourses about communities in society, including LBGT+ people.

Methods

The authors were guided by the fundamental question ‘What is the Problem Represented to be?’ (WPR) which is an approach to critical policy analysis (Bacchi & Goodwin, 2016). They aimed to explore the way the suicide ‘problem’ is represented in government debate and policy, positioning it as a ‘product’ of political practices.

As part of a broader study on the politics of suicide and suicide prevention, parliamentary proceedings and relevant suicide prevention documents for England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland from 2009-2019 were thematically analysed. Through this primary analysis the authors found that LGBT+ people were very often represented as a group with higher rates of suicidality and suicide, who require specialist suicide prevention support.

Prompted by this finding, they then undertook a further analysis and discovered that 79 of the parliamentary debates mentioned LGBT+ suicide. They combined this data on LGBT+ suicide with that from their analysis of eight suicide prevention policy documents from England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland (two from each of the UK nations). Guided by the WPR approach, the dataset was thematically analysed, and the research team discussed similarities and differences.

Results

‘Statistical invisibility’

The research investigation uncovered a problem characterised by ‘a cycle of statistical invisibility’. The lack of figures on LGBT+ suicide, suicide risk and evidence on intervention effectiveness is used in some policies as a reason to justify marginalising LGBT+ people in suicide reduction efforts and to explain a lack of specialist support provision. However, the policies in question do not call for action to improve this situation.

Conceptualisations of ‘risk’

While the language of risk is used in policy to support the argument for more appropriate suicide prevention services for LGBT+ people, risk construction often ignores the context. In these cases, risk is located within the individual and suicide is seen as a ‘pathological state’. Positioning LGBT+ people as inherently ‘risky’ can mean disregarding the external structural influences on extreme distress, health inequalities and potentially impede the scope of suicide prevention services.

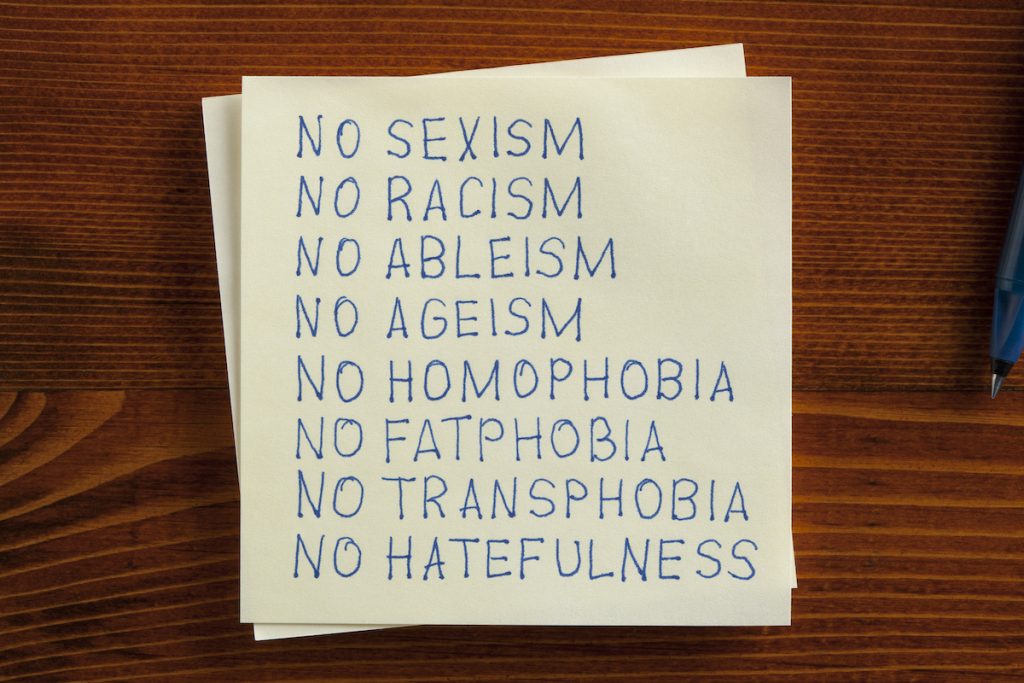

‘Hate kills’

Policies and debates regarding suicide prevention among LGBT+ people often discuss stigma, bullying and discrimination, something particularly evident in discussions on young LGBT+ people and bullying in schools. Here the bully is positioned as an external contributor to the risk, but the problem is located with individual pupils and schools. However, some policy discussions acknowledge the wider societal influences and expectations that shape bullying, and recommendations to incorporate anti-hate approaches in LGBT+ suicide prevention strategies.

‘Suicide as a tool of rhetoric’

Significant progress in LGBT+ rights was made over the ten years in question, including legislation to allow gay and bisexual men who were convicted under laws that criminalised homosexuality to be ‘pardoned’ and equal marriage. Debates over marriage reforms surfaced hostile, homophobic views. LGBT+ rights supporters argued that such expressions contributed to wider social stigma and prejudice, which could in turn affect LGBT+ suicidal distress. The authors say that this argument acted as a ‘rhetorical warning device’.

The analysis of parliamentary debates and UK policies showed that LGBT+ suicide is pathologised, but also seen as a byproduct of hate activities.

Conclusions

In their research, the authors discovered a ‘dichotomised representation’ of the ‘problem’ of LGBT+ people and suicide where it is ‘…either internally attributable to LGBT+ individuals, or as externally attributable to perpetrators on queerphobic hate’.

They call for a greater nuance in LGBT+ suicide prevention policy making and argue that:

To better understand, and indeed prevent LGBT+ suicide…internalising, psychological approaches and externalising, social approaches to understanding LGBT+ suicide must be brought into dialogue with one another.

Finally, they conclude that:

…policy makers and politicians must work together to provide support for individuals experiencing suicidal distress through the provision of community and clinical resourcing.

Policy makers and politicians must address the wider systemic influences on the suicidality of non-heterosexual and gender diverse people.

Strengths and limitations

The authors do not outline strengths and limitations in the paper. Undoubtably, the research reveals some important findings on the nature of policy making and how dichotomous understandings of LGBT+ suicide can make for policy disjuncts that have serious practical implications.

The investigation is grounded in the broader historical context where ‘perceptions of sinfulness, criminality and pathology’ have influenced social and political responses to non-heterosexual and gender diverse people who experience mental distress. The authors present a critical policy analysis method that could be used to examine parliamentary debates and policies concerning other groups who have been prey to similar malign influences. For example, if it isn’t already being done, perhaps a similar study on the effects and consequences of racialisation, racism and ‘neo-colonial constructions of mental illness’ (King, 2016) in mental health policy should also be undertaken.

The research addresses ‘LGBT+’ suicide. The phenomenon of ‘lumping’ together diverse people has been highlighted for sexualities research, with researchers advising that this risks masking the diverse needs and experiences within a defined group, creating gaps in the evidence (Kneale et al, 2019). The paper would have benefitted from discussion of this. Some of the terminology used could have been more clearly defined. For example, the term ‘queerphobia’ may not be familiar to readers. Further explanation of this overarching term and how it encompasses diverse experiences of homophobia, biphobia and transphobia would have been helpful, perhaps in relation to ‘lumping’.

The clear definition of terminology used to describe diverse experience in the paper would be helpful to the readers and the interpretation of the analysis.

Implications for practice and policy

The research findings have direct implications for LGBT+ suicide prevention policy and practice. The authors are clear that the two contrasting ways in which LGBT+ suicide is conceived should be brought together so more nuanced and effective approaches are taken to prevention, and the complexities of LGBT+ people’s suicidal distress more fully considered.

According to the study, research evidence on the effectiveness of LGBT+ suicide prevention strategies and services appears to be lacking. Improvements in data collection practice need to be made, but as the authors’ critique of ‘quantification’ attests, figures are just one form of evidence. If we are to come to a fuller understanding of LGBT+ suicide and suicide prevention, we also need to draw on experiential and practice evidence.

A wealth of knowledge is held by suicide survivors, LGBT+ mental health organisations and specialist practitioners who should directly participate in making the policies that concern them. Participatory social policy determines that ‘where people need…support…they have a real say in that process, instead of having someone else’s moral, ideological, economic or social solutions imposed on them’ (Beresford & Carr, 2018 p.1). Marzetti and colleagues offer a case study in why such an approach is urgently needed.

The study highlights the clear need for suicide prevention strategies tailored for sexually diverse populations within clinical services and social policies.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Marzetti, H., Chandler, A., Jordan, A., & Oaten, A. (2023) The politics of LGBT+ suicide and suicide prevention in the UK: risk, responsibility and rhetoric, Culture, Health & Sexuality, DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2023.2172614

Other references

Bacchi, C. & Goodwin, S. (2016) Poststructural Policy Analyses – Guide to Practice, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Beresford, P. & Carr, S. (2018) Introduction, in Beresford, P. & Carr, S. (eds.) Social Policy First Hand Bristol: Policy Press pp. 1-11.

Cameron, C. (2018) Social policy and disability, in Beresford, P. & Carr, S. (eds.) Social Policy First Hand, Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 51-61.

King, C. (2016) Whiteness in psychiatry: the madness of European misdiagnoses, in Russo, J. & Sweeney, A. (eds) Searching for a Rose Garden, Monmouth: PCCS Books, pp.69-76.

Kneale, D. et al (2019) Conducting sexualities research: an outline of emergent issues and case studies from ten Wellcome-funded projects, [version 1; peer review: 3 approved]. Wellcome Open Res 2019, 4 (137),

Scott, P. (1958) Psychiatric aspects of the Wolfenden Report: 1, The British Journal of Delinquency, 9 (1) pp.20-32.

Source link

#problematic #politics #LGBT #suicide #prevention