Cancer Screening Guidelines Lack Information on Harms

,

by Nadia Jaber

In a review of 33 cancer screening guidelines, researchers have found that the guidelines don’t adequately capture the potential harms of cancer screening. Providing information on harms is critical so people can have informed discussions with their health care providers about screening, the researchers noted.

Screening tests, such as mammograms, HPV or Pap tests (also called Pap smears), and colonoscopies, check for cancer or precancerous growths in people who don’t have any symptoms of the disease.

By finding precancerous growths before they turn into cancer or finding cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage, screening tests can reduce deaths from cancer.

But screening can also cause various harms including physical harm, worry and stress, inaccurate results, and unnecessary follow-up procedures. (See the box below for a list of potential screening harms.)

For those reasons, screening is recommended only when the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms, said Paul Doria-Rose, Ph.D., chief of NCI’s Healthcare Assessment Research Branch.

“If there’s overwhelming evidence of a net benefit of a screening test, we don’t want to scare somebody off” from getting screened, Dr. Doria-Rose said.

“But by the same token, if there’s a risk that [a serious harm] could happen if you have a screening test or a follow-up diagnostic test, then it’s a physician’s obligation to inform patients about what the risks of those procedures are,” he said.

In the NCI-funded study, Dr. Doria-Rose and his colleagues looked at commonly used guidelines for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer screening to see whether various harms were mentioned and, if so, if they were described briefly or in detail.

Information on screening harms in those guidelines often fell short, the researchers found. For example, some harms were not mentioned at all, while others were mentioned only briefly.

The study was published September 27 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The study results “bring attention to the inconsistency across guidelines,” said Louise Davies, M.D., a thyroid cancer surgeon at The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice and Veterans Affairs Medical Center in White River Junction, Vermont.

“The analysis may allow different guideline bodies to compare themselves and identify areas they hadn’t previously considered,” said Dr. Davies, who wasn’t involved in the study.

Comparing the benefits and harms of cancer screening

To create a cancer screening guideline, a medical organization convenes a panel of experts to compare the benefits of a screening test with the harms.

The benefits tend to be narrowly defined as either preventing death from cancer or preventing a precursor (like a polyp in the colon) from turning into cancer, Dr. Doria-Rose explained.

But the potential harms of cancer screening are more complex and harder to measure, he said.

They run the gamut of physical, psychological, emotional, and financial effects. Plus, those harms can come not just from the screening tests themselves, but also from follow-up tests and treatments.

Some harms are more serious than others and might carry more weight in the comparison, Dr. Doria-Rose continued.

For instance, serious bleeding following a colonoscopy would be weighted more than the pinch of a blood draw for a PSA test.

Also, as many screening experts stress, most harms tend to occur during or soon after a person gets screened, while the benefits don’t show up until many years later.

So, when guideline developers compare the potential benefits of a screening test with its potential harms, “obviously it’s not an apples-to-apples kind of comparison,” he said.

Evaluating US screening guidelines

The researchers evaluated cancer screening guidelines from more than 10 medical organizations, including the US Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

They found that none of the guidelines had complete information on the potential harms of screening. Guidelines for prostate cancer screening were the most complete, whereas those for colorectal cancer screening were the least complete.

“Certainly, a lack of high-quality research on the harms of screening contributes to this variation,” Russell Harris, M.D., M.P.H., and Linda Kinsinger, M.D., M.P.H., wrote in an editorial on the study.

But the study also showed that reporting of harms was inconsistent even between guidelines for the same type of cancer. For instance, some cervical cancer guidelines mentioned the potential for unnecessary diagnostic tests while others didn’t.

“We worry about a tendency [for guideline developers] to underrecognize the importance of harms,” Drs. Harris and Kinsinger wrote.

How often do screening harms happen?

In agreement with earlier studies, the researchers also found that very few of the guidelines gave a clear idea of how many people typically experience each harm associated with a particular screening test.

Providing the frequency of a harm makes it easier for people to compare harms and benefits and make an informed decision, Dr. Doria-Rose explained.

For example, according to one analysis, screening 10,000 women for breast cancer every year for 10 years starting at age 60 will prevent 43 deaths from breast cancer (88 women will still die from breast cancer despite getting screened). It will also result in nearly 5,000 false positives that lead to nearly 1,000 unnecessary biopsies.

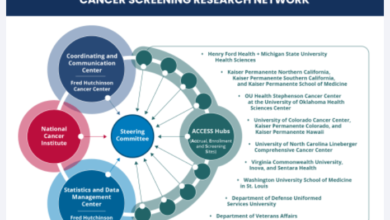

More research is needed to learn how frequently some screening harms happen, especially in community health care settings, Dr. Doria-Rose noted. That’s one area of focus for NCI’s PROSPR network, he added.

Finally, the researchers noted that while the benefits of screening were often calculated for multiple rounds of screening over many years, the guidelines almost never considered the harms of screening in the same cumulative way.

That makes the task of comparing benefits and harms like “comparing apple slices to [whole] oranges. We only have a piece of the picture,” Dr. Doria-Rose said.

There’s currently not enough research on the cumulative harms of cancer screening, Dr. Davies said. More studies in this area would be “very important because it would provide balanced information for patients to make informed decisions,” she added.

A need for greater transparency

Based on their findings, the research team suggested two calls to action for guideline developers.

“We’re encouraging [guideline developers] to do deeper dives before they update their guidelines the next time, to make sure that they’re really using the best possible evidence [on screening harms] to make their recommendations,” Dr. Doria-Rose said.

The second is a call for greater transparency about how guideline developers make their recommendations.

“Be open about what harms you’re considering and what harms you’re not considering, and what benefits you’re considering and not considering, so that at least we know what the screening recommendations are based on,” he said.

Drs. Harris and Kinsinger also advocate for greater transparency. “Whose values does the panel use to balance benefits and harms?” they wrote.

For example, are the lives saved by screening valued more than preventing unnecessary biopsies?

Each guideline likely reflects “what the [panel of] clinicians values most from their own experience in treating the cancers in their field,” Dr. Davies noted.

But guidelines should also consider the values of the people who are getting screened, she said.

“I think there’s a role for improved representation by stakeholders who are not clinicians—patients, family members, people who’ve had both positive and negative screening experiences,” Dr. Davies continued.

Ultimately, many experts believe it’s important for each person to decide what matters most to them when considering getting screened.

Every individual should be able to “choose to follow those [guidelines] that apply values most similar to their own,” Drs. Harris and Kinsinger wrote.

Source link

#Cancer #Screening #Guidelines #Lack #Information #Harms