Cancer Research UK – Science blog

Children’s cancers present very different challenges to adult ones. So do cancers in teenagers and young people.

That gets right to the heart of our work. In order to give young people, teenagers and children with cancer the best chance of survival without side effects, we have to approach their diseases differently.

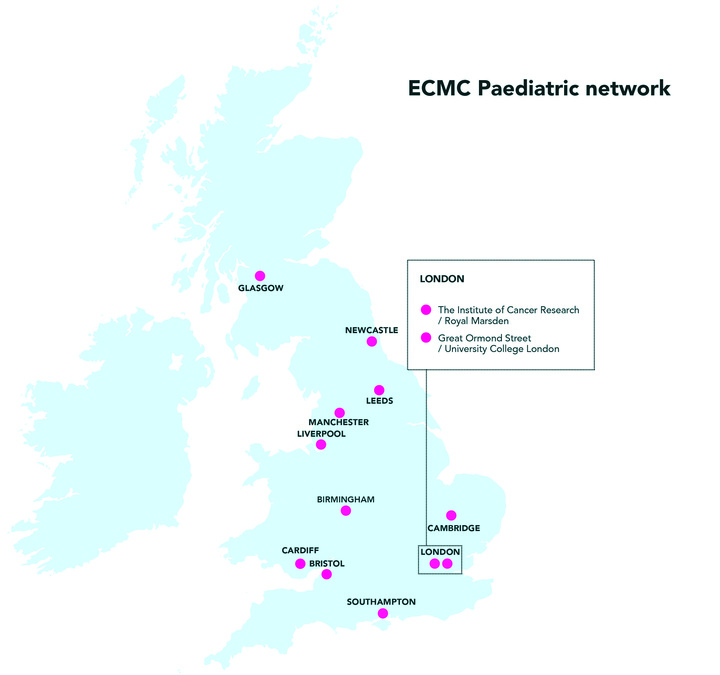

Our network of paediatric Experimental Cancer Medicine Centres (ECMCs) makes that possible. When conventional treatments aren’t working, ECMCs give children with cancer, as well as young people up to the age of 24, access to trials testing promising new medicines that aren’t available anywhere else. And, in doing so, they help doctors and researchers find more effective and less toxic drugs.

Ultimately, ECMC network trials bring the medicines of the future closer to the children and young people of today.

And now, for the first time, The Little Princess Trust is providing a substantial investment, partnering with us and the devolved health departments – the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the Chief Scientific Office in Scotland and Health & Social Care Wales – to help support and develop the network.

For the 5 years from 1 April 2023, charity and government are contributing a total of £6.6m to the paediatric ECMC network. That’s almost three times the amount from the last 5-year period.

Teiva’s story

Teiva rests during her cancer treatment. Dawn Collins

Teiva Collins, 13, was diagnosed with a type of blood cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) in 2019. She has finished her chemotherapy treatment but still faces ongoing challenges due to its side effects.

Teiva has received the Cancer Research UK for Children & Young People Star Award and is also an Ambassador for The Little Princess Trust.

Her mum Dawn said: “We welcome anything that might help other families in the future, and it is good to see Cancer Research UK and The Little Princess Trust working together. More clinical trials are needed so that treatments can improve.

“Teiva has always shown incredible courage and bravery, with a smile on her face, and such politeness for all of the doctors and nurses, but the ongoing issues are taking their toll.

Teiva has finished treatment, but is still dealing with side effects. Dawn Collins

“So many things have happened to her to knock her down – adrenal gland problems, COVID, constant nausea, gastrological problems, pain in her legs and feet, and much more besides. We are still investigating the issues she is facing and as a mum I will always worry.

“Teiva, from the very beginning, was keen to be open and honest about her cancer, so we started an Instagram page to document her journey and raise awareness for charities that have been hugely helpful and supportive. We couldn’t be more proud of her.

“We hope that this funding will help bring about progress.”

How will this help children and young people with cancer?

With the extra money, the ECMC network will expand to include a new centre in Cardiff. That means fewer children and young people in Wales will need to travel to England to receive experimental treatments. Trial designs will get more patient-friendly, too – with the network supporting tests and scans at local hospitals as well as the 12 ECMCs.

The new funding will also pay for the development of a data platform that brings together all the information we can gather about people’s individual cancers. Doctors will be able to use it to match patients to the trials that are most likely to help them.

Plus, over the next 5 years, the ECMC network will also be focusing on using its data to improve how we use established drugs. By monitoring how patients who are ‘hard to treat’ respond to cancer medicines, the sites will be able to work out the best ways doctors across the country can care for understudied groups like newborn and premature babies.

And, of course, the money will also ensure the network can train and employ more of the specialist nurses, researchers and data managers it needs to carry out innovative clinical trials built around the needs of patients. With new specialists at every site storing and processing patient samples, it will be easier for every study to leave a legacy that improves future treatments, too.

In other words: there’s a lot happening. To better understand what all this could mean for the 4,200 children and young people diagnosed with cancer every year in the UK, we spoke to two researchers whose pioneering trials have been supported by the paediatric ECMC network.

Making trials easier for patients and families

Guy Makin, a paediatric oncologist and senior lecturer at Manchester University NHS Trust, has helped steer the paediatric ECMC network for over a decade. He’s not taking credit for its achievements, though. The secret to success in treating children’s cancers has always been teamwork.

“There’s not many children with cancer in the UK, and less than 20% of them are ever going to need experimental treatments,” he explains. “And that means the number of children who can take part in trials is quite low. So, we all want to put our patients into the same trials, because we all want to know what the best treatment is.”

For that to happen, trials need to be as visible, accessible and patient-friendly as possible. That takes planning. Before the ECMC network launched, many trials were only open at a single (often London-based) site, which made joining difficult for people who didn’t live locally. Now, though, every trial is open in at least one centre in each of the network’s 4 regional areas.

Over the coming years, that ‘decentralised’ structure will strengthen the connections between the network and the rest of the health system. “We’re trying to make sure that we can deliver these trials with as little disruption as possible to maximise the number of patients who join,” Makin says. “If having to travel for a scan or a test is a barrier for a family, then let’s do it locally.”

Families are the experts in what works best for them. That’s why the ECMCs are also expanding their work with parents and patient representatives. Their input helps make trials as easy and accessible as possible for children and young people – no matter who they are, where they live, or what cancer they have.

Giving doctors the data they need

There’s another side to this, too. Even medical professionals sometimes need help keeping track of trials.

Across each of its regions, the ECMC network has established a formal process for doctors to get together and discuss the best options for young patients who relapse or don’t respond to established treatments. It ensures doctors across the country are aware of the trials their patients can join.

“Before, that was quite a barrier,” Makin adds. “People just wouldn’t know about the trials that were open.” That slowed recruitment, meaning it could take longer for effective drugs to become standard treatments for children’s cancers.

These ECMC ‘relapse panels’ are also fully integrated with our Stratified Medicine Paediatrics (StratMedPaeds) study. Using advanced information from tumour samples, StratMedPaeds matches young patients to the experimental treatments most likely to help them.

“That’s been very, very successful,” says Makin, who stresses that it wouldn’t be possible without ECMC network-funded research nurses. “We’ve managed to go from not really having any information at all about tumours at the time of relapse, to molecular profiles for over 600 patients.”

So far, these profiles, which are generated at the Royal Marsden in London, have been shared and discussed with doctors in online meetings. Now, though, the tests we can do on patient samples are beginning to provide more useful information than it’s possible to cover in a Zoom call.

“We need to have a better way of managing it than just a meeting,” Makin points out, “so we now have funding to develop a data integration platform that links everything together.

“The doctor will be able to see that for this patient, at this point in their disease process, this is the best type of treatment, and it’s available through trials at these ECMCs.”

Doing more for the very youngest children with cancer

The data collected by the paediatric ECMC network isn’t just relevant for trials of new drugs. It can also improve how we use established treatments.

That’s thanks to a collaboration with the Newcastle Cancer Centre Pharmacology Group (NCCPG), led by Professor Gareth Veal. Their work is also funded by us, The Little Princess Trust and the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

The NCCPG’s ‘therapeutic drug monitoring’ service looks at how anticancer drugs work in patients that are difficult to treat. This can include infants and premature babies, children and young people with kidney problems or obesity, and those who need particularly high doses of chemotherapy.

“We’re giving doses, monitoring what happens, and then adjusting to make sure we get the dose that’s actually correct, rather than too little, which won’t be effective, or too much, which will cause too many side effects,” explains Makin. “And, because we collect all that information, the NCCPG can use it to model what will work for other patients and come up with guidelines.”

These guidelines are already helping doctors outside the ECMC network make the best decisions for their own young patients. Over the next 5 years, this work will be expanded to cover more drugs and tumour types, and the guidelines will be developed into an online tool that will make the whole dosing and monitoring process much easier.

Improving immunotherapy for children and young people

But ECMCs also test drugs with the potential to completely change how we treat cancer in children and young people.

Dr Sara Ghorashian specialises in some of those medicines. She works at Great Ormond Street Hospital and University College London. Her clinical trials focus on using immunotherapy to treat leukaemia.

Immunotherapies work by guiding our immune systems to fight cancer. Ghorashian’s main interest is in a type called CAR T-cell therapy, where doctors take immune cells from patients and modify them so they can recognise cancer cells. When they’re put back, these altered T-cells guide the immune system to attack cancers that it couldn’t even see before.

CAR T-cells are tuned to target cancer cells. Design_Cells / Shutterstock.com

That’s a very complicated and difficult process. CAR T-cells have already changed how we treat some children’s cancers – the NHS now uses them to help some children who, like Teiva, are affected by ALL – but it can take a lot of very precise and expensive testing to make sure they work well for as many people as possible.

So, Ghorashian has been thinking about how to make CAR T-cell trials easier.

“You have to go back to the drawing board again and again before you get something that works,” she explains, “and the only way that you’re going to know what’s going to work is if you collect relevant samples. They’re how you understand how to make the therapy better.”

Early phase immune therapy studies are often very expensive to run, so it can be difficult to cover the cost of collecting and storing key samples for the longer term. That’s where the ECMC network is stepping in.

“Every large immunotherapy centre can now have a full-time person to bank samples, which can be used to improve the immunotherapies in the next generation of trials,” says Ghorashian. “It’s a relatively small amount of resource, but the potential to create a biobank of samples that are relevant to these early phase clinical studies is huge.”

The difference a trial can make

Ghorashian’s team is currently working hard to optimise new types of CAR T-cell therapies for ALL. They’re trying to improve outcomes for patients receiving immunotherapy, and they’re showing why ECMC support is so important.

We’ve known for a while that, to work best against ALL, CAR T-cells need to stay in the body for a long time.

“It means that you can deliver the CAR T-cell therapy on its own, and you don’t have to keep on treating the kids with other toxic treatments like bone marrow transplants,” Ghorashian explains.

But there’s no shortcut to making long-lasting CAR T-cells. Good research can take a long time – especially if researchers don’t have a smooth way of transitioning from one trial into the next.

Ghorashian’s team had that transition. It’s helped them find new approaches to some of the biggest challenges in CAR T-cell therapy.

“We did another study before, which was less successful, but the lessons we learned from it were absolutely invaluable,” she says.

With the support of the ECMC network, other immunotherapy researchers will have the same opportunity to build on previous trials. Even apparently unsuccessful studies will play a role in developing safer and more effective ways to help young cancer patients.

“The ECMC funding makes it feasible to run expensive clinical studies,” says Ghorashian. “We can do little things to manage the toxicity or improve how we deliver the cells, and something that didn’t work can start making a difference.”

The differences she’s talking about can save lives. They can also make lives easier to live – free from side effects like hearing loss, organ damage and infertility.

There’s 5 years of those differences ahead.

Tim

Source link

#Cancer #Research #Science #blog