how do adolescents with emotional difficulties cope?

Worldwide epidemiological data suggests that about one third (34.6%) of mental disorders (including emotional difficulties like depression and anxiety) start before 14 years of age, and two-thirds (62.5%) by age 25. However, the Children’s Commissioner in the UK (2022) tells us that only one third (32%) of young people who need help with their mental health, can access specialist care, due to barriers like long waiting times, limited resources, and rejected referrals. We’ve heard this many times, but it’s clear that the mental health needs of children and adolescents are not being met.

The UK is increasingly promoting lived experience, patient involvement for shared decision-making, and self-care strategies, such as digital resources or guided self-help. Unsurprisingly, the self-help industry is often viewed as profit-motivated, and their universal implementation and effectiveness are debated. Hence, Town and colleagues (2023) conducted a scoping review of the available literature to refine the definition of self-help, self-care, and self-management, tailoring them to adolescents’ emotional needs.

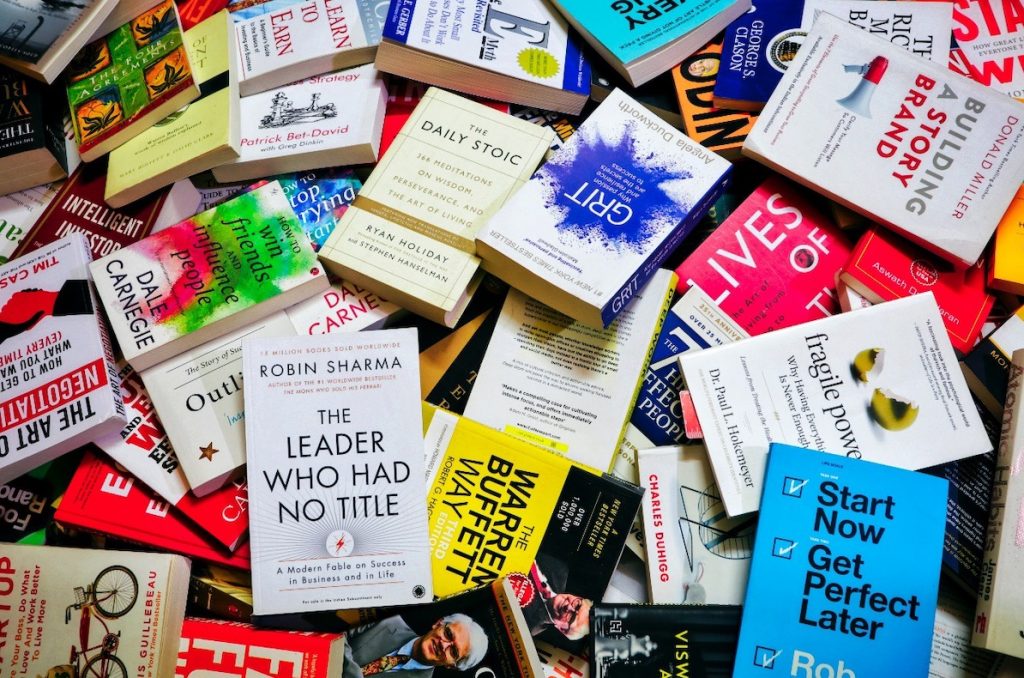

Self-help books, and psychoeducation websites, are self-help interventions that adolescents use alongside professional therapy.

Methods

The authors used the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology adhering to the PRISMA-ScR standards. Databases included PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL Plus, and Mednar (with backward checking). The search strategy (adapted for each database) identified search terms by checking literature and discussions with a research librarian. The authors only considered studies published in English (or with an accessible English translation) from 2000 onwards. They excluded guided interventions and any constructs and interventions unrelated to self-management, self-care, or self-care. Conference abstracts, presentations, and commentaries (non-empirical evidence) were also excluded. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts with strong agreement. The kappa statistic was found to be 0.87 (strong) during stage one, and 0.62 (moderate) during stage two.

The authors synthesised the evidence using a narrative approach and a reflective thematic analysis by Brown and Clarke (2006; 2019) to discuss findings narratively.

Results

Initial searches returned 11,231 records, of which 4,418 were duplicates. Of these, 6,572 were excluded after scanning titles and abstracts, and 248 were excluded following a scan of the complete text. Across the different stages, reasons for exclusion included interventions being guided (n=82); participants’ age mismatch (n=55); self-care, self-management, and self-help not being mentioned (n=48); non-empirical studies (n=480); and other reasons (n=19). Of the 62 studies included in the analysis, 32.25% were quantitative studies, 22.58% were systematic reviews, 16.1% qualitative studies, 8% review papers, 6.45% book chapters, 3.22% dissertations, 3.22% meta-analysis, 1.61% scoping reviews and 1.61% systematic reviews. Most of the articles referenced self-care (n=6), self-management (n=17) and self-help (n=51).

The reflective thematic analysis of 62 papers generated a total of 12 themes:

- Digitally available;

- Monitoring, managing, and preventing symptoms;

- Associated with clinical treatments or interventions;

- Can involve social elements;

- Daily activities to improve health;

- Looking after yourself;

- Seeking professional help when needed;

- Can be static;

- Reduces stigma, cost, and burden, and increases access;

- Tailored and engaging;

- Agency and empowerment;

- Learning from feedback and problem-solving.

The only common theme across self-help, self-care, and self-management was “Digitally available”.

The authors also associated strategies within the reflective analysis to each of their concepts to answer the two scoping review research questions.

1. How are the concepts of self-management, self-care, and self-help described in the context of adolescents with emotional problems?

Within the context of adolescents with emotional problems, the three concepts demonstrated overlapping yet distinct characteristics.

Self-management revealed a single clear definition within the literature, which overlapped with some definitions of “self-help”, suggesting their principles merge. Nevertheless, self-management emphasises agency, empowerment, problem-solving, learning from feedback, and regular activities like monitoring symptoms and adherence to treatment.

Self-care extended such regular activities to include sleep, diet, and exercise. However, it had no clear definition within the literature. Suggesting that the concept is more conversational than evidence-based and thus requires further investigation and clarity in its application to adolescents with emotional problems. Moreover, self-care was clearly defined for adolescents with diabetes, implying the term could be context-dependent.

Self-help was the most defined concept, with five definitions suggesting the concept has been historically strengthened. Some of these definitions highlighted that self-help is associated with digital interventions, like computerised cognitive behavioural therapy. Also, such interventions reduce stigma, increase treatment provision cost-efficiently and enhance and facilitate access to mental health support. Other definitions emphasise how self-help is the actions adolescents can take independently without seeking professional help.

2. What strategies or techniques have been proposed to facilitate self-management, self-care, and self-help in adolescents with emotional problems?

Although the focus of the study was on “self”, the strategies and techniques found within the literature evidenced that some were shared across concepts and could be grouped within two broader categories “self” and “community approaches”. The authors concluded that digital availability was a shared strategy across all three terms. This highlights how adolescents prefer digital help-seeking that does not require professional intervention. Moreover, interventions highlighted across concepts included technology-empowered cognitive behavioural therapy (tCBT) and programmes like Rainbow SPARX, a tool designed for LGBTQ+ youth. Accessibility was enhanced, amongst others, with the content being web-based, app-based, or in the form of audio, text, or video (i.e. DVD).

Self-management strategies emphasised daily activities and routines that would best manage conditions to minimise their impact. For example, problem-solving and learning from feedback, as well as mobile interventions facilitated self-management through everyday message reminders and mood tracking; which would indicate emotional problems need structured and proactive approaches.

Self-care included self-implemented strategies, like stress balls, mindfulness, or breathing techniques to alleviate emotional distress. Moreover, it yielded the largest number of techniques and strategies, which began with one self and extended to involve peers and family members in search of support. This clearly suggests that social support plays an important role in self-help.

Digital technologies are the favoured self-help method for adolescents.

Conclusions

Literature on adolescents with emotional difficulties often discusses the concepts of self-help, self-care, and self-management with overlapping definitions and strategies. However, despite the concepts being different in their interpretation or definitions, the implemented strategies were found to be quite similar. This scoping review consolidated these ideas and supported previous studies suggesting such strategies should be divided into two broader categories: “self” and “community approaches”. The authors indicate further research into the terms is needed to best support adolescents’ unmet mental health needs –especially for marginalised groups, like the LGBTQ+ community.

Further research is needed to understand self-care and collective care for adolescents from the LGBTQ+ community.

Strengths and limitations

The comprehensive inclusion of empirical studies, unpublished papers, and grey literature ensured a broad scope that had not been conducted before. This reinforced the knowledge base with an exhaustive review of overlapping concepts in the context of adolescents experiencing emotional difficulties. The screening of literature was conducted by two researchers and strengthened by a high degree of agreement, suggesting a consistent and trustworthy study evaluation. Lastly, the scoping review highlights the potential of digital interventions, especially for marginalised groups. Such emphasis is significant, given that these groups often face unique challenges and disparities in mental health support.

However, the concepts under study need more specificity beyond facilitating strategies, suggesting further research is needed to avoid potential misinterpretations. Hence, we can only be confident that this review only provides a preliminary framework rather than a complete conceptualisation of the concepts. There is a clearly disproportionate representation of “self-help” literature compared to self-care and self-management, making any true comparisons challenging – especially for self-care. The potential cultural differences influencing the three concepts remain unexplored.

How are self-care and self-help conceptualised across different cultural contexts?

Implications for practice

The concepts of self-management, self-help, and self-care, when related to adolescents with emotional challenges, share considerable similarities in their definitions and strategies. It would be beneficial for clinicians to consider these strategies collectively under broader categories like “self or community approaches”. Understanding this unified perspective can offer clarity and more streamlined approaches to intervention planning as tools and techniques might be transferable or adaptable across domains. Clinicians can inform ‘keeping well’ plans at the end of their treatment, risk management plans, or behavioural activation with strategies tailored to the preferences and needs of their service users.

While these strategies hold promise across diverse adolescent populations, this study also identified a significant gap regarding tailored approaches for marginalised groups, notably LGBTQ+ young people. The preliminary evidence suggests potential for interventions targeting depression within these populations, but the limited geographical scope of current studies signals a need for more expansive research. Therefore, clinicians should actively seek out the latest research, and where possible, advocate for or participate in research initiatives that can provide a broader understanding of effective strategies.

In essence, while the unified understanding of self-help, self-management, and self-care can guide general intervention strategies, a nuanced approach is essential when addressing the unique and potentially amplified challenges faced by adolescents with emotional difficulties and marginalised youth.

Ongoing research on self-help, self-care, and self-management can help deliver targeted and effective digital interventions for young people.

Statement of interests

The author of this blog declares that they have no competing interests or conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Links

Primary paper

Town, R., Hayes, D., March, A., Fonagy, P., and Stapley, E. (2023) Self‑management, self‑care, and self‑help in adolescents with emotional problems: a scoping review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

Other references

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., and Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). “Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies” in Molecular psychiatry, vol., 27, no., 1, pp., 281–295.

World Health Organization. (2019). “International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision” in, ICD-10, Version:2019, 10th ed.

American Psychiatric Association (2010). “Axis, I disorders” in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders, fourth edition DSM-IV, Washington, DC.

Children’s Commissioner (2022). “Children’s mental health services 2020/21” in Briefing on Children’s Mental Health Services – 2020/2021

Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., and Soares, C. B. (2015). “Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews” in International Journal of evidence-based healthcare, vol., 13, no., 3, pp., 141–146.

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., Godfrey, M. C., Macdonald, T. M., Langlois, V. E., Soares-Weiser, K., Moriaty, J., Clifford, T., Tuncalp, O., and Straus, E. S. (2018). “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation” in Annals of internal medicine, vol., 169, no., 7, pp., 467–473.

Braun, V. Clarke, V. (2006). “Using thematic analysis in psychology” in Qual Res Psychol , 3, no., 2, pp., 77–101.

Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2019) “Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis” in Qualitative Res Sport, Exercise Health, 11, no., 4, pp., 589–597.

Wolters, L. H., Op de Beek, V., Weidle, B., and Skokauskas, N. (2017). “How can technology enhance cognitive behavioral therapy: the case of Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder” in BMC Psychiatry, vol.,17, no., 1, pp., 226.

Lucassen, M. F. G., Merry, S. N., Hatcher, S., and Frampton, C. M. A. (2015). “Rainbow SPARX: a novel approach to addressing depression in sexual minority youth” in Cognitive and Behavioural Practice, vol., 22, no., 2, pp., 203–216.

Photo credits

Source link

#adolescents #emotional #difficulties #cope