COVID information seeking linked to poorer mental health

The WHO has officially lifted the Public Health Emergency of International Concern status for COVID-19 whilst suggesting that the virus remains a global threat (Wise, 2023). Since the wake of this pandemic, we have also witnessed a massive infodemic – an excessive amount of information concerning a problem – with the public navigating vast quantities of information.

Reportedly, most people, especially during the first stages of the pandemic, would check the latest updates on the pandemic first thing in the morning (Choi & Jeong, 2021). While generally information-seeking has been viewed as an adaptive coping strategy to reach informed decision-making (Wang et al., 2021), health information-seeking has been linked to higher anxiety sensitivity (Norr et al., 2014) and overly frequent health information-seeking behaviours are often linked to high levels of health anxiety, contributing to a vicious cycle of reinforcement (Peng, 2022).

Recent research on COVID conspiracy theories has highlighted a “culture of mistrust and suspicion”; showing that as many as one in four people in England “endorse unequivocally false ideas about the pandemic” (Freeman et al, 2020).

Reporting on data from the UK COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing study, a national longitudinal survey that ran from March 2020 to July 2021, Wilding et al. (2022) examined whether COVID-related information-seeking was linked to symptoms of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and well-being.

Is frequent information seeking on COVID-19 linked to worse mental health among the UK population?

Methods

This paper was part of the UK COVID-19-MH study “tracking the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and wellbeing of people within the UK” (O’Connor, n.d.). The detailed methodology of the UK COVID-19-MH study can be found in O’Connor et al., (2020) and in O’Connor et al. (2022) and the main research questions were preregistered at AsPredicted.org.

Registered members of a UK panel (Panelbase.net) were invited to participate using a quota sampling method for a sample representative of the UK population with quotas based on age, gender, socioeconomic grouping (The National Readership Survey social grade, n.d.), and region of the UK. Data was collected at 6 time points (TPs); 3,077 participants completed the first wave, with a sample representative of the UK population based on age (18–24 years: 12%; 25–34: 17%; 35–44: 18%; 45–54: 18%; 55–64: 15%; ≥65: 20%), gender (women: 51%; men: 49%), socioeconomic grouping (SEG; assessed via The National Readership Survey social grade; AB: 27%; C1: 28%; C2: 20%; DE: 25%, based on occupation, where A, B and C1 are higher and categories C2, D, E are lower) and region of the UK (12 regions). From the final sample, 1,945 (63.2%) participants completed the survey at all six waves (TPs 1-3 within the first 6 weeks of the UK lockdown; TPs 4-6 approx. every 2 to 3 months). Apart from the demographic details, information on the following was collected:

- Information seeking on COVID-19 (“How often do you actively seek out information on COVID-19?”)

- Depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire)

- Generalised Anxiety Disorder symptoms (GAD-7)

- Mental Wellbeing (Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale)

- Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale)

- Mental health status measures as the existence of mental health conditions, neuro-divergent disorders or alcohol/drug problems

- Physical health status, measured as the existence of physical health conditions.

Chi-square tests were used to examine the relationship between information-seeking frequency and the demographic groups. Hierarchical linear modelling was used to examine the relationship between COVID-related information-seeking and mental health outcomes as well as loneliness (effect size as adjusted β). The researchers also performed tests using the clinical cut-offs to indicate high levels of depression, anxiety, and loneliness and low levels of wellbeing using hierarchical Bernoulli models (effect size as Odds ratio).

Results

COVID-related information-seeking over time

- Information-seeking frequency reduced over time, as the majority reported looking for information less than once a day towards the end of the study

- The percentage of individuals searching for information more than six times a day towards the end of the study was significantly lower as well.

Information-seeking across different groups

- Individuals belonging to the higher socioeconomic groups (SEGs) reported seeking information more frequently compared to the individuals in the lower SEGs (at all six TPs)

- Women reported seeking information more frequently than men later on after the onset of the lockdown (TPs 3-6)

- Individuals over 30 years old reported seeking information more frequently compared to those under 30 years old (TPs 2, 3, 4 & 6).

Information-seeking and mental health outcomes

- More frequent reported COVID-related information seeking was linked to higher levels of self-reported depressive and anxiety symptoms, more loneliness, and worse mental well-being across the 6 TPs

- More frequent COVID-related information seeking was linked to at least moderate levels of depression (OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.014 to 1.280), anxiety (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.066 to 1.375) and wellbeing (OR = 1.12, 95% CI 1.003 to 1.248), but not loneliness

- Mental health status – whether the participants had pre-existing mental health disorders, neuro-divergent disorders, or alcohol/drug problems – was not linked to any differences between COVID-related information seeking and depression, anxiety, or loneliness.

Women, individuals from higher socioeconomic groups, and individuals under 30 reported seeking for COVID-19-related information more frequently.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

higher levels of information seeking were associated with poorer mental health outcomes, particularly clinically significant levels of anxiety.

“Information seeking during the COVID-19 pandemic was related to poorer mental health outcomes and particularly pronounced for anxiety”.

Strengths and limitations

The current study builds upon the important literature on the complexities of health-related information-seeking. More specifically, the study provides evidence in the context of COVID-19, where misinformation and fake news have been the norm. This data collected over an extended time provides evidence for a longitudinal relationship over the first year of the UK lockdown, but we cannot conclude on the directionality of the relationship, but can perhaps hypothesise that the relationship between information-seeking and anxiety is reciprocally reinforcing.

The study findings are generally in line with a previous meta-analysis of online health information-seeking behaviours, which suggested that females and individuals with higher levels of income and/or education were more likely to engage (Wang et al., 2021), except for age. This might be indicative of a context effect, as younger individuals might have been more concerned with the measures and restrictions of the lockdown compared to the health-related information.

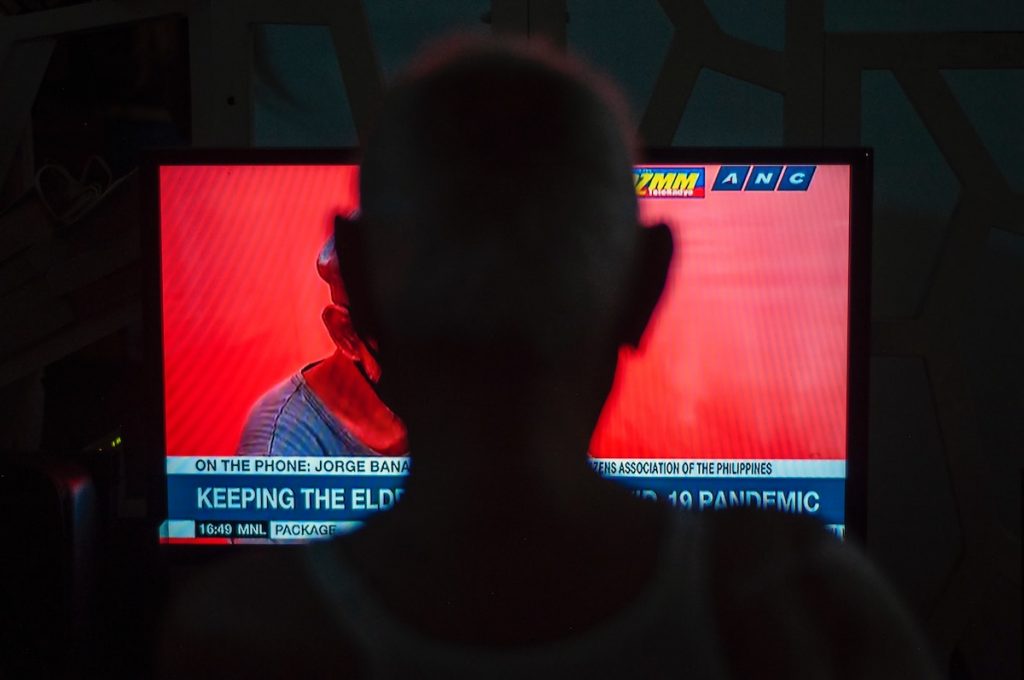

The authors highlighted the importance of understanding the effect of health information seeking in times of uncertainty, amidst a surge of fake, inaccurate, and often manipulated information. This type of information can only trigger negative emotional and psychological reactions which contribute to experiencing depression and anxiety. While the researchers comment on the potential role of the media (e.g., social media vs. medical websites) used to seek information, as well as the specific sources (e.g., graphic images vs. text), the study did not collect this information. As a result, we cannot conclude whether this has been in fact important in the case of COVID-19. Thus, it was not possible for the authors to (a) identify if certain channels/forms of content were linked to worse mental health outcomes or (b) propose targeted interventions focused on specific channels/forms of content.

The large sample size and the sampling method add to the representativeness of the population and lay a foundation for the generalisability of findings. The research findings are representative of the UK population and should be considered with caution in comparison to other countries. According to Wang et al. (2021), the level of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) development in the country where information-seeking behaviour takes place affects information-seeking behaviours and their effects on individuals. It is important to highlight here that most of the research is usually carried out in Western and developed countries (‘WEIRD’ populations), especially as during the pandemic health inequalities between high and low-middle-income countries became more apparent.

Lastly, the use of self-report measures increases the chances for common-method bias that can inflate the relationship between exposure and outcomes. Recall bias could also be affecting self-rated measures, as is known by research in the field of social media usage (Parry et al., 2021).

The study did not identify if certain channels and/or forms of content were linked to worse mental health outcomes.

Implications for practice

The findings can inform future research and practice on both individual and societal levels:

- During times of uncertainty, mental health practitioners should actively educate their clients about the potential consequences of excessive health information-seeking. This can include behavioural interventions, such as controlled/limited exposure to news and social media at specific times of day and/or breaks from information overload.

- Moreover, the study also supports the need to promote social media literacy skills to help young people and adults critically evaluate the information they encounter and discern credible sources vs. misinformation.

- Practitioners can also encourage individuals to nurture their social support networks, as well as their self-care routines. Positive interactions can limit and counterbalance the negative impact of excessive information-seeking.

The authors highlighted that targeted management of information-seeking behaviours could potentially assist in reducing anxiety and improving well-being, especially in cases where a vast amount of (largely unreliable) information is available. Research into how information-seeking can trigger/maintain worry and rumination will allow targeted interventions to alleviate the associated symptoms, particularly among individuals over the clinical threshold for anxiety and depression. Policymakers and the scientific community should focus on encouraging community members to limit information-seeking as a way of protecting their mental health. More specifically, multi-disciplinary collaborations between clinicians, healthcare institutions, public health agencies, and news outlets are needed to disseminate accurate and balanced information and provide expert input in shaping public communication strategies during crises.

The scientific community should focus on encouraging people to reduce or manage their information-seeking behaviour as a way of protecting their mental health and well-being.

Statement of interests

I have no competing interests to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Wilding, S., O’Connor, D. B., Ferguson, E., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., O’Carroll, R. E., … & O’Connor, R. C. (2022). Information seeking, mental health and loneliness: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing study. Psychiatry Research, 317, 114876.

Other references

Choi, H., & Jeong, G. (2021). Characteristics of the measurement tools for assessing health information–seeking behaviors in nationally representative surveys: Systematic review. Journal of medical Internet research, 23(7), e27539.

Freeman, D., Waite, F., Rosebrock, L., Petit, A., Causier, C., East, A., . . . Lambe, S. (2020). Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychological Medicine, 1-13. doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001890

National Readership Survey (n.d.). Social Grade. Accessed at: https://nrs.co.uk/nrs-print/lifestyle-and-classification-data/social-grade/

Norr, A. M., Capron, D. W., & Schmidt, N. B. (2014). Medical information seeking: impact on risk for anxiety psychopathology. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry, 45(3), 402-407.

O’Connor, R. (n.d.). UK COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing study. Accessed at: https://suicideresearch.info/tracking-the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-mental-wellbeing-study-covid-mh/

O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., O‟Carroll, R.E., O‟Connor, D.B., Platt, S., Scowcroft, E., Watson, B., Zortea, T., Ferguson, E. & Robb, K. A. (2020). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1-8.

O’Connor, D. B., Wilding, S., Ferguson, E., Cleare, S., Wetherall, K., McClelland, H., … & O‟Connor, R. C. (2022). Effects of COVID-19-related worry and rumination on mental health and loneliness during the pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Journal of Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2022.2069716

Parry, D. A., Davidson, B. I., Sewall, C. J., Fisher, J. T., Mieczkowski, H., & Quintana, D. S. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(11), 1535-1547.

Peng, R. X. (2022). How online searches fuel health anxiety: Investigating the link between health-related searches, health anxiety, and future intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 136, 107384.

Wang, X., Shi, J., & Kong, H. (2021). Online health information seeking: a review and meta-analysis. Health Communication, 36(10), 1163-1175.

Wise, J. (2023). Covid-19: WHO declares end of global health emergency. BMJ 2023;381:p1041

Photo credits

Source link

#COVID #information #seeking #linked #poorer #mental #health