Cancer Research UK – Science blog

This article follows on from part one of the women in science pioneers series, in which we celebrate women who have contributed to impactful discoveries in the field of cancer research.

In this second article, we’re celebrating some more pioneering women who have helped to improve outcomes for people with cancer and paved the way for more innovative research.

Professor Dame Valerie Beral

Dame Valerie Beral Credit: The History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group Queen Mary University London

Professor Dame Valerie Beral accomplished a huge amount in her long and illustrious career. She was one of the first to suggest that cervical cancer might be linked to an infection, and even established that Kaposi’s sarcoma was caused by a sexually transmitted infection in people with AIDS – but not by HIV.

But her most notable impact was in the field of women’s health. Beral helped to unpick the risks of the contraceptive pill, finding that while it does slightly increase breast cancer risk, this is only temporary and returns to baseline levels 10 years after the pill is stopped.

She later went on to demonstrate that the oral contraceptive pill reduces the long-term risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers. These findings have reassured millions of users of the contraceptive pill around the world, and enabled people to make more informed choices.

Beral helped to unpick the risks of the contraceptive pill

That might be enough for most people, but Beral wasn’t done there. She also established the Million Women Study, the largest of its kind in the world which includes 1 in 4 of all UK women born between 1935 and 1950. It has contributed to countless valuable insights, from helping to establish whether HRT increases the risk of cancer, to understanding the role of factors such as alcohol intake and smoking in cancer.

As well as being an exceptionally talented epidemiologist, Beral was also a keen mentor. She took a special interest in supporting women in science to fulfil their potential and take up senior positions in science. The impact of her research and mentorship will be felt for many years to come.

You can read more about Dame Valerie Beral in our tribute article.

Dr Anne Szarewski

Dr Anne Szarewski

Although there had been suggestions that cervical cancer could be linked to a virus, the relationship between human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer wasn’t fully established until Harold zur Hausen’s work in the 1980s.

The Papanicolaou test (or smear test) was already being used by clinicians to screen for changes in cells in the cervix that could lead to cervical cancer. But even when cells in the cervix show up as abnormal, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll lead to cancer. So researchers wondered whether there was a way to predict which abnormal cells were at higher risk of developing into cancer.

And that’s where Dr Anne Szarewski comes in.

Szarewski joined the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (one of the two forerunners of Cancer Research UK) in 1992 as a clinical research fellow. She worked with Dr Jack Cuzick on cervical cancer.

In 1995 a paper was published, for which Szarewski was the clinical lead, that showed that testing for the presence of HPV DNA on cells taken during cervical screening would pick up pre-cancers that were missed by smear tests.

Szarewski followed this study with a larger multi-centre trial using a commercially available HPV test. The HART study was published in 2003. One year later the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) recommended the use of HPV testing in primary cervical screening. HART’s results were central in this decision.

Two decades later, cervical screening programmes around the world routinely use HPV testing.

Szarewski was also one of the first to study the possibility of HPV testing on self-collected vaginal samples. This approach could reduce several barriers to uptake and may help to reduce inequalities in cervical screening.

Szarewski played a key role in HPV vaccine research

She also played a key role in HPV vaccine research, becoming the lead investigator for the team who developed the first vaccine. It was approved in the EU in 2007 and the UK government first introduced routine HPV vaccination for girls in 2009. Szarewski also advocated for the vaccine to be given to boys as well as girls.

The impact of the HPV vaccination programme has been enormous. In fact, recent research has shown that that the HPV vaccine dramatically reduces cervical cancer rates by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at ages 12 to 13 in England.

You can read more about Anne Szarewski in our tribute article.

Professor Nandita deSouza

Professor Nandita deSouza

Professor Nandita deSouza, academic radiologist at The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) and The Royal Marsden, pioneered the use of a new imaging technology, known as endocavitary probes for use with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), for improved diagnosis of cancer.

Traditional imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT or standard MRI techniques are useful for diagnosing cancer but the images are often not very detailed, and their use is limited in some parts of the body.

Knowing the precise location and size of a tumour is very important when it comes to planning treatments. And that’s where endocavitary MRI probes can help. These imaging devices can be inserted into the body to provide high quality images of cancer tissue.

Since they bring the receiver closer to the region of interest, they provide much higher resolution images.

This is particularly important when assessing early-stage or small cancers.

For example, high-resolution images of the cervix are particularly critical for mapping the extent of small cervical tumours, as this can determine whether someone is considered for fertility-sparing operative treatments.

Initial results using endocavitary probes for cervical cancer were impressive, showing that they can help detect more tumours compared to external scans. These results have a big impact on dictating surgical courses of action in early-stage disease.

This technology has also been beneficial for people with prostate cancer. Endocavitary probes can detect prostate tumours that are often not identifiable with standard imaging and are useful for assessing whether they will progress.

deSouza pioneered the use of endocavitary probes with MRI for improved diagnostics

deSouza has also worked on developing a less invasive way of tracking myeloma – a type of blood cancer that develops from cells in the bone marrow. She demonstrated that using MRI scans to take a whole body ‘snapshot’ is a safe way to monitor how tumours in individual bones are responding to treatment. This is hugely beneficial as it can help to reduce the need for invasive biopsies and blood tests.

She also brought high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) treatment to patients at The Royal Marsden. This has been used to treat cancer pain as well as the tumour itself when it has come back. Many people who have cancer that has spread to the bone can experience intense bone pain. HIFU is a very precise treatment that works by using heat to destroy the nerve endings in the membrane around the bone tumour which is causing the pain, while leaving nearby areas unharmed.

Throughout her career, deSouza has worked to develop standards for MRI measurements, chairing and contributing to imaging biomarker standards committees at an international level. She also advises and participates in European clinical trials committees.

deSouza has a major interest in mentorship for women in academic medicine and worked through the Women in Academic Medicine Committee to develop a process for part-time and flexible training for academics. She was also heavily involved in the Athena SWAN programme at the ICR.

Dr Yvonne Barr

Dr Yvonne Barr Credit: Balfour et al. 2020

In the early days of cancer research, it seemed unthinkable that cancer could be caused by a virus. Now, though, we’ve learned that the best way of preventing cervical cancer is to immunise young women against HPV. So, how did we get here?

It’s largely thanks to Dr Yvonne Barr. She helped discover the first virus that could cause cancer, which came to bear her name – the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

In 1963, Barr joined the lab of Anthony Epstein, a virologist who specialised in electron microscopy – a powerful technique that produces high resolution images on the nanometre scale. A pathologist named Bert Achong was also part of the lab, whose electron microscopy skills also came to play a crucial role.

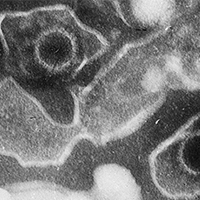

Electron microscopic image of two Epstein Barr Virus virions (viral particles) Credit: Liza Gross, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

A surgeon called Dennis Burkitt had reported a type of cancer that was common in young children living across central Africa – later named after him as Burkitt’s lymphoma. He noted a strong geographical pattern that matched particularly rainy areas with high temperatures year-round. The similarity to the pattern of malaria led Burkitt and colleagues to believe that the lymphoma was being transmitted by an insect-borne virus.

After delivering a lecture in London, Burkitt met with Epstein and arranged for samples of tumours taken from children with Burkitt’s lymphoma to be shipped from Uganda to Epstein’s lab in London.

Barr helped to culture the samples. Then, using an electron microscope, the team examined Burkitt’s lymphoma and were able to see that some of the cells were filled with tiny virus particles – a virus that would come to be known as the Epstein-Barr virus.

This discovery opened up a whole new field of research. EBV infection was strongly linked to cancers of the back of the nose and throat. Further studies showed that testing for EBV could flag people who had the virus but no symptoms and help spot those at higher risk of cancer.

After completing her PhD studies, Barr moved to Australia, where she completed a Diploma of Education and taught Biology in secondary schools.

According to historian Gregory Morgan – author of the book ‘Cancer Virus Hunters: A History of Tumor Virology’ – Barr “left the field of research, in part, because of her experience with sexism.”

Looking forward

The women highlighted in these articles are just a few of the amazing researchers who have helped pave the way for future women in cancer research. And while women around the world have been making groundbreaking discoveries in cancer research for decades, often their work does not gain the recognition it deserves.

Change is happening gradually. The scales have started to tip in favour of female students in education with female graduates being consistently highly represented in the life sciences, often at over 50%. However, barriers remain in place and women are still underrepresented at more senior levels in research.

At Cancer Research UK we’re dedicated to removing these barriers, and have set up initiatives like our Women of Influence programme to help empower women in science to become leaders in their field.

Stay tuned for future articles in our women in science series, where we will highlight some of the barriers faced by women in research, as well as celebrating some of the rising stars of cancer research.

Source link

#Cancer #Research #Science #blog