Addressing the Promise and Challenges of Big Data

Guest post by Hisham Hamadeh, PhD, and Shawn M. Sweeney, PhD

Imagine a world where many of the decisions we make today are smarter. A world where your next pivotal experiment, your clinical trial design or amendment, and your decisions about which medicine to prescribe or take, are all informed by the entirety of the available relevant data. What if the volume and diversity of big data is converted to knowledge that helps support the choices you have to make? This is the promise of big data, and while we are not quite there today, we may not be that far away either.

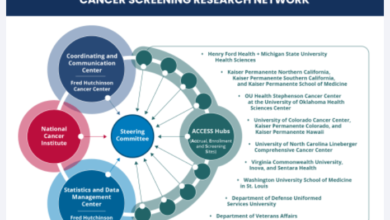

During the past two years, we have had the privilege of co-leading an august group of experts, including representatives from international regulatory agencies, pharmaceutical companies, academia, health care systems, and patient advocacy organizations. The group was convened by the Foundation for the NIH (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium Cancer Steering Committee, and was charged with synthesizing a series of recommendations regarding democratization of health care data. The question that guided us: How can we use all the data that patients have entrusted us with to change not only their lives, but the lives of others who may be experiencing a similar journey? The results of these efforts have culminated in two review articles just published in Cancer Research that highlight a diversity of issues associated with big data in health care and provide a number of real-world use cases that address the problems as exemplars.

What exactly is big data? There are nearly as many definitions as there are potential users and practitioners. The general sentiment, however, points to data at large enough volume, velocity, and variety that exceed the capabilities of typical relational databases and analytic frameworks to generate actionable knowledge or insights. Additionally, the veracity, or quality, of the data is critical to ensuring it can be analyzed, (re)used, and trusted to enable “smart” decisions.

We are at a point in history where data is being generated at an unprecedented pace, particularly in the life sciences sector. Health records, medical images, provider notes, and ‘omic data have grown in size, complexity, and fragmentation. In parallel, there is logarithmic growth in the sophisticated algorithms being applied to analyze data, generating derived variables and novel representations of the original data that act as a multiplier, further contributing to volume and velocity.

The majority of data, however, continues to be siloed, due to a host of technical factors (such as data formatting, term harmonization, permission to access, etc.) and human behavioral factors (such as control, competition, poor regulation on the monetization of health care data, etc.). Compartmentalization of data prevents the realization of the full potential of the collective resources, and in the instance of patient data, may be in direct opposition to the intent of patients who consented to the generation and use of their data.

Patients living with cancer, like our co-author Liz Salmi, have a sincere desire to have their medical experience shared with others in order to help achieve increasingly superior outcomes for people navigating similar journeys. Despite the implied trust that patient data will be used in an honorable fashion, many questions remain, including concerns about re-identification, monetization, and whether patients will be notified when their data contributes to a breakthrough.

Aggregating various data sources is one of the fastest ways to attain the volume and variety of data needed to power decision-making. The Blue Ribbon Panel convened as part of the original Cancer Moonshot, commissioned by the Office of the President of the United States, recognized this, and at least three of the panel’s recommendations involved data sharing. While data sharing is not a specific focus of the reignited Cancer Moonshot, several of the pillars would be enhanced by data sharing efforts, particularly those involving rare and pediatric cancers.

Fortunately, there are recent improvements in data sharing for the purposes of improving patients’ lives through better medicines, quality of life, and addressing emerging health threats. As an example, on October 6, the U.S. code of federal regulation (45 CFR 171.103) expanded the definition of electronic health information, meaning that health care organizations must provide patients with access to their full health records in a digital format.

We recognize that there is no such thing as best practice. We strived to offer good practices in our manuscripts to provide a framework for consideration as you embark on your next data generation or collection effort, and we hope that you prioritize ways to disseminate your data to help others inform the best decisions they can for the benefit of patients everywhere.

Editor’s note: The authors would like to thank Calais Prince, PhD, associate director of Science and Health Policy at the AACR for her insight and review of Cancer Moonshot activities.

Shawn M. Sweeney and Hisham Hamadeh are co-chairs of the Foundation for the NIH (FNIH) big data group. Sweeney is the senior director of the AACR Project GENIE Coordinating Center and project lead, having served the project since its inception. Hamadeh is currently Vice President and Global Head of Data Sciences at Genmab. He has previously served on a Scientific Advisory Committee for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Source link

#Addressing #Promise #Challenges #Big #Data